PRINCIPAL'S ESSAY CHARTS THE EARLY HISTORY

OF

LISBURN INSTITUTE 90 YEARS ON

|

Ninety years old and the Institute is still a great asset to Lisburn | |

|

|

|

|

|

An early hockey team from Lisburn Institute |

|

|

|

|

THE principal of Lisburn Institute has produced an essay that charted the establishment and early day of technical education in Lisburn between 1901 and 1920.

Alister McReynolds charted the history of the 'tech' as Lisburn Institute celebrated its 90th anniversary with a special ceremony at Lagan Valley Island last month.

The broad content of the essay is as follows: Technical education developed in Ireland during the first two decades of the 20th century.

The first major step in its growth was taken with the passing of the Local Government (Ireland) Act of 1898, and the next step came in 1899, with the passing of the Agriculture and Technical Instruction(Ireland) Act.

|

|

This marked the start of the technical education system. in Ireland, for the Act established the Department of Agricultural and Technical Instruction. Horace Plunkett, who played a major part in the Co-operative movement and in the establishment of the Irish Agricultural Organisation Society in 1894, was appointed vice-president of the Department.

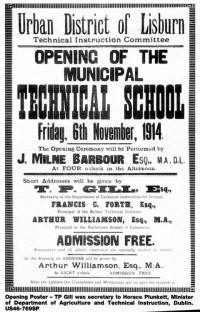

The initial success of the Department of Agricultural and Technical Instruction must largely be credited to Vice-President Plunkett, who received a knighthood in 1903, and T.P. Gill, its secretary.

As regards the Lisburn school, it was Gill who was to play the major part, as he retained the secretaryship until the partition of Ireland, while Plunkett left the Vice-Presidency in 1907.

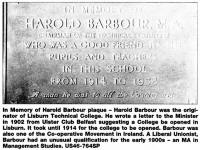

The notion that Lisburn should have a technical school was first mooted in 1901. The suggestion was contained in a letter from Barbour to Gill, written from the Ulster Club, Belfast, on 11 February.

Gill replied to Frank Barbour on 16 February 1901, stating that the maximum grant for the Lisburn school would be �600 initially, for materials and equipment.

After Dixon's meeting with the Council in September 1902, there followed years of correspondence between Council and Department. In the main, this consisted of the former asking if the latter would subsidise Lisburn pupils' train fares, in order that they might attend technical studies classes in Belfast. Proximity to Belfast was an advantage for Lisburn from an industrial point of view but was now militating against the town's motivation to develop it own technical education scheme.

Lisburn Urban District Council did not again address the question of developing its own scheme until October 1912. On the fourth of that month, Town Clerk, Mr. T. M. Wilson, wrote to Gill, asking for copies of schemes for other towns. Gill replied that he would prefer to send the Inspector of the Ulster District to meet a committee appointed to draw up a scheme for the area.

There is no record of response to Gill's suggestion until 5 April 1913, when Mr Robert Bannister, a member of the Council wrote to Gill, asking questions about how to obtain �600, whether the town had to supply the building and fit it out, the minimum number of schemes and what the penny in the pound would be used for.

Gill's reply indicated that the penny in the pound might be used towards renting a suitable building and drew Bannister's attention to the fact that Banbridge, Carrickfergus, Lurgan and Portadown, all with smaller populations, that Lisburn had by now developed technical schools.

Discussion

Eight months later, the council decided to act. On 3 November 1913, a newspaper report of the following day stated that 'a long discussion took place, relative to the question of adopting the Technical Education Act, as a result of which, they unanimously they recommended the council to adopt the Act'.

The recommendation was accepted and passed unanimously. A statement of intention made with regard to obtaining a property in Castle Street, known as Castle House, by paying rent for a term of years. Just under a month later, this special committee offered to rent Castle House at £60 per year for two years, with the option of purchasing the building at the end of the agreed period for £1,500.19.

In the eyes of the Department, however, the committee were moving too quickly, as they had not been properly constituted under the conditions of Section 14 of the 1899 Act.

By March 1914, the. situation had been resolved and the first meeting of the Technical Education Committee was held in Lisburn Town Hall.

The suggested scheme for Lisburn, as outlined by Dr Garrett, the Inspector from the Department, 'comprised domestic, commercial, engineering and building classes; also linen weaving and spinning.' It was also that a principal be appointed and an advertisement for the position was duly placed in the press.

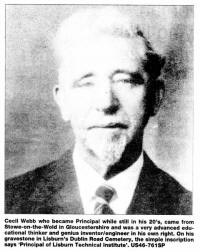

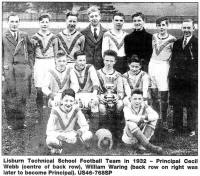

Out of 50 applicants, the committee decided on Cecil Webb, a remarkable man. A more appropriate phrase might be 'a remarkable young man', for he was only 35 years old and had by then been Principal of Clonmel Technical School, Co Tipperary for nine years.

Novelty

A keen motorcyclist he brought his motorbike with him to Ireland, where it was regarded as a threat rather than a novelty by the populace of Tipperary. According to his grandson, he was actually denounced from local pulpits for introducing what many regarded as a satanic contraption. Local people stretched a rope across the road to ensnare him and a local cleric, on one occasion, turned his horsewhip on him, presumably to drive out the devil from man and machine!

Webb took up his position on 1 July 1914 and by October 1914, he had a telephone installed in Castle House, the purchase of which was finalised by the following January, for �2,000.

The school was formally opened by J Milne Barbour D.L. on 6 November. Gill was among the guests at the ceremony. In his congratulations to the town on 'coming into line with other towns in the matter of technical instruction, he left no doubt as to where he felt the blame lay, regarding Lisburn's lateness of adopting a scheme. 'Lisburn, it must be admitted, took some time to make up its mind'.

Evening classes had already begun on 19 October, with subjects ranging from domestic economy to an introductory course on damask weaving.

In 1915, Webb began to develop his own curriculum, as a response to the community's needs. His first idea was for the creation of a dap commercial school.

This was intended for pupils who had reached the seventh standard of the National School, or were 15 years old.

The scheme was duly submitted, with the committee's agreement. However, shortly afterwards, Webb decided to postpone it because of the school's overdraft.

By the start of 1916 Thomas Dunne was appointed temporary Commercial Instructor for the 1916-17 session.

For some six months later Webb was of the opinion that the day Commercial school was not a viable financial undertaking and was not inclined to recommend a permanent appointment.

Nevertheless, by the following year, Dunne's position, and that of the scheme, had become permanent, judging from the fact that he was now paid an annual sum of �156 and was included in the school's salary list.

Webb's proposal curricular innovation in the field of motor engineering also met with the problem of lack of finance. His plan, in fact, was to create a Motor Engineering School in Lisburn.

The Department, however, initially refused to sanction the

scheme. Webb's disappointment was seen in a later letter to

the Department.

Lisburn, in fact, eventually did develop a Motor Engineering

School, in 1917. Under its auspices, half the apprentices in

Ireland who had obtained scholarships in motor engineering

under the Department's scheme, were to receive their training

in Lisburn.

As regards training for Lisburn's thriving textile industry, local textile employers were generous in their donations of machinery and money to purchase the same. Various members of the Barbour family were particularly prominent in this respect. Webb was profoundly grateful for such generosity, which went a considerable way towards enabling the school to offer a variety of training in this particular field. Webb's debt to his Lisburn benefactors was not simply a material one, however, for Milne Barbour actually appears to have had a considerable input into the curriculum for textile training.

An example of this is the latter 's suggestion. that the course should include a wide variety of processes such a preparing and spinning flax, bleaching and dyeing, plain and damask weaving, and marketing the products. He also suggested training in subsidiary skilled trades such as mechanical and electrical engineering and millwrighting.

It is worth remembering that the school's important and formative years were those of wartime, which event was inevitably reflected in the life of the institution at times. In November 1914, the Committee offered the use of 14 rooms in the school wing to the Belgian Relief Committee, to house refugees. The offer, however, was not taken up. The following year, the committee considered the desirability of using the school workshops to manufacture hand grenades or other war material. Webb had, in fact, prepared machines to turn out such weapons. When it became obvious, however, that orders for munitions were to be forthcoming, no further plans for war work were mooted.

1920 was a significant milestone in the history of technical education in Northern Ireland after responsibility for it was transferred to the new government which had been established under the Government of Ireland Act 1920.

Close to home, it was also momentous in the history of Lisburn and of the school itself, for, on 22 August, District Inspector O R Swanzy of the Royal Irish Constabulary was shot dead some 300 yards from the Tech., as he left church.

This unhappy event was just one incident in a series of sectarian murders which had flared up in Belfast from 21 July, as the tensions of the Anglo-Irish war in the south swept over Ulster.

Swanzy, recently transferred from Cork, had been deemed responsible by the IRA for the death of Cork's Lord Mayor, Thomas MacCurtain. After his murder, Lisburn was engulfed in riots and Roman Catholic homes were burnt.

All told, the period from June to September 1920 saw 22 civilians killed in Belfast, with riots in Lisburn, Banbridge, Dromore, Ballymena and Bangor.

The school did not escape this strife and tension. In April 1921, Webb reported to the committee that 'owing to the losses resulting to the school from the disturbed condition of the town following upon the Swanzy murder,' he thought it would be two or three years before they would be in so favourable a financial position again.

Recover

The school, of course, did recover, as did the town. The backlash of the murder, however, emphasised how strongly outside events could influence the school and detract from the aims of the technical education movement.

Webb retired in 1941 after 27 years, during which his enthusiasm and energy helped place the school in the forefront of educational life in Lisburn.

Principals since have been Dr R C Fox, Mr J Waring, Mr D Wright, M J H McDowell, Dr K Baird and Mr A McReynolds (current Principal).

Today Lisburn Institute of Further and Higher Education has 5,000 students studying subjects ranging from computer studies to digital photography and mechatronics.

The Institute uses the most advanced computer and robotic technology.

As befits the emphasis on education for all, the Institute is also engaged in a mayor reskilling and rural development scheme for farmers and those living in Lisburn's rural hinderland. Truly Lisburn Institute can be said to be a vital and important asset to the city of Lisburn and its community - a fact which has not altered since its opening 90 years ago.

31/12/2004