- Front Page

- Chapter one

- Chapter two

- Chapter three

- Chapter four

- Chapter five

- Chapter six

- Chapter Seven

- Chapter Eight

- Chapter Nine

SKETCH OF THE LATE MR. A. T. STEWART.

THE COTTON FAMINE OF 1862-'63

PART SECOND.

A. T. Stewart's Shop 1844

MOST men who have made special way in the world retain very vivid recollections of their first appearance behind the counter. The heiress whose " coming out" in the fashionable world forms a sort of landmark in her existence, and the dramatic debutante while leaving the green-room for the footlights have each their wild emotions of hopes and fears; but, though not so exciting in its action, the young trader has his own share of sensational dreamings about the future as he starts in the race for the commercial " blue ribbon." A. T. Stewart, in his after days, and when he stood at the head of the whole republic of shopkeepers, thus describes the dull, dreary-looking September morning which ushered him into the world of trade :-

" I rose early, as usual, but was disheartened by the weather. About seven o'clock I went to the store. There was no sign of life outside. The streets were deserted. I entered the building and retired at once to my private room. There I sat silent and alone until I heard one of my shopmen asking for me. I opened the door, and then he said the rain was ceasing. Soon after a gleam of sunshine broke out. This greatly cheered me. My hopes revived still more when the same young man announced that there were several persons at the door. It was now eight o'clock, and he asked me if he should let them in. `Not until nine,' I said. The crowd began to increase rapidly. As the time drew near for throwing open the doors I felt more and more anxious. A few seconds before nine I quitted my room, and took up my position at the extreme end of the building, that I might watch the incoming crowd. When the doors were opened there was a rush of people just like a Jenny Lind night at the opera. I was much affected at the sight. The unexpected brightening of the day, and the concourse of people in consequence, produced a reaction upon me, and I confess that I withdrew quietly to my room again, and I found relief in having a good cry."

One of the great powers in creating success in business is that of the head of any house, whether large or small, having the good fortune to obtain the assistance of efficient, upright, and well conducted hands to aid him in carrying out his course of enterprise. From the day of his commencement A. T. Stewart was blessed with such co-workers. He paid first-class hands good salaries, and in return demanded the most efficient service.

When he started in mercantile life John Jacob Astor was said to be worth several millions or dollars, and the next richest citizen of New York was possessed of immense wealth in steamboat property. The situation of the new concern was not considered as happily chosen. Hudson Street had then the reputation of being the most important locale for the retail dry goods business, but not a vacant concern was to be had there. It fortunately happened, however, that 283, Broadway was just next door to a fashionable emporium owned by a foreigner named Bonafantie, and where the Upper Ten made their purchases of articles of vertu, which, in beauty of design and exquisite workmanship, bad no equals in the city. The attractions of that bazaar of the arts drew crowds to the neighbourhood, and Stewart's unique display of the fanciful in textile products had its share of admirers and customers. Each article offered at the store was marked in plain figures ; and the cabalistic words, " No Second Price" —painted in large letters over a little archway that spanned the lower section of the concern dividing the lace from that of the linen and muslin department—attracted the utmost attention.

The system was novel, for in those days the mode of sale in dry goods. and, indeed, all other wares, was for the storekeeper to ask so-much for his merchandise and the customer to higgle for getting it at less. Many worthy citizens were not a little astonished at the hard and fast lines by which business was done in "No. 233, Broadway," and the inquiry, " Is A. T. Stewart a Quaker?" might frequently have been heard. It is a fact, however, that the embryo millionaire's residence in the house of Thomas Lamb, of Pear Tree Hill, and his boyhood companionship for several years with the sons of his guardian, John and Joshua, had the effect of giving to his general character much of the peculiar habits that mark the personal history of the disciples of George Fox.

Still the fair sex of New York, as well as the country belles of the same State, found little difficulty in arriving at the conclusion that the "No second price" mode of sale as carried out at the Broadway store was generally on terms under those charged in most other concerns, while the style of article was much superior. Rapid was the turn-over, and as the young merchant had entertained some prescience of the future, and placed several orders for forthcoming supplies from the Old Country, large imports followed, and the stock was fully kept up by an amplitude of fresh goods.

But the attractions of Stewart's store did not end with the beauty of the fabrics on sale or the system of fixed values. One of the proprietor's commercial principles was that of what might be called conventional republicanism. The servant maid, or " help," who went to the store for the purpose of buying a cotton dress, had an entire line of such fabrics laid before her, and was as deferentially looked after by the chief or his assistants as was the up-town lady when engaged in the purchase of the highest priced production of the looms of Lyons. In course of doing business, the young men connected with 283, Broadway, were expected to shew the goods on sale to the best advantage, but in no case did Mr. Stewart permit any exaggerated account to be given respecting the quality of the goods.

As all transactions were effected on the ready cash system, the capital employed did the work of three times its amount under a range of credit accounts. Manufacturers competed with each other for the custom of the rising merchant; and at the end of his second year, the space of the store became so inadequate that he was obliged to rent a large concern in one of the back streets, where all the extra stock was kept until required to assort that on immediate sale. In the meantime, he kept himself and his wares prominently before the fashionable folks of the city, and the State of New York as well, by a regular system of advertising through the papers. Every large consignment of goods from Europe—the linens of Ulster, the printed cottons of Lancashire, the laces of Valenciennes, and the brocaded silks of Paris—had due announcement; and the crowds of purchasers that thronged to the store told how well the selection of goods suited the tastes of his fair customers.

In 1825, Mr. Stewart married Miss Cornelia Clinch, daughter of a very wealthy ship chandler of New York. The young lady had received a very good education, but in the course of that sowing of intellectual seed the duty of industry had not been forgotten, and immediately after having taken upon herself the responsibilities of a wife she set about aiding in the transactions of the store, as it on her own exertions much of the future success depended. It has been said that, on the delivery of the goods which her husband was in the habit of purchasing at the auction sales, she would re-finish parcels of gloves and also the lots of lace so perfectly, that they appeared as if just from the hands of the manufacturer.

The concern, as already stated, had ceased to accommodate the customers and contain the stock, and during the three years previous to the autumn of 1832 A. T. Stewart had made two removals, in each case to larger places of business. No. 257, Broadway, was an extensive store, situate between Murray and Warren Streets, and this had been fitted up with great care and taste, the young merchant's classical education having given him a love of the decoration that was seen even in his selection of fancy fabrics. Nine years' successful commerce had made him a person of civic celebrity and a wonder to the plodding speculators of Wall Street.

A T Stewart Home - Fifth Avenue - NYC

All this time, and amid the great excitement that could not fail to follow his unexampled success, he never forgot the more than ordinary affection he felt for his mother. The second husband of that lady had died, and once again, and for the third time, she had entered into what are called in the Episcopal Service " The holy bonds of matrimony." Her son, James Bell, went to sea many years before, and, it was supposed, had gone down with the ship in which he sailed , and her daughter Mary was no more. At the time, therefore, to which I refer, she and her new husband were the sole occupants of a small house in a quiet part of the Hudson-washed city.

John Turney bequeathed the good-will or tenant-right of a fourteen-acre

farm to his grandchildren, James and Mary Bell. The property was to be

disposed of by his trustees and the proceeds placed at interest, which

interest was to be paid his widow for her life, and then to go to the

legatees when they came of age. Mrs. Turney died in May, 1825. The farm had

sold at ten pounds the acre; but as Mr. Stewart had not heard anything of

the purchaser, in whose hands the proceeds of sale remained, he wrote the

following letter :—

![]()

"New York, October 7, 1832.

"Mr. William Dillon, Lisburn.

"DEAR SIR,—When I had last the pleasure of seeing you, I think you said you would assist me if necessary in obtaining certain moneys belonging to the estate of the late John Turney, of Lissue, who died in April, 1815. These moneys were left to James and Mary Bell, my half-brother and sister. The latter died without issue. James Bell left this city in May, I8I8, for South America, and from thence he sailed in the brig Union, which vessel has never been heard of since. My mother is still living, and married again, to a gentleman named John Martin. The farm my grandfather left the two children was sold for £140 sterling to a man of the Maze, named N. Dickson. This person has since died ; but before his death he wrote my mother, then Margaret Bell, to say that, provided she would give him security that he would not again be called upon, he would pay the amount to whoever she might appoint to receive it, or else he would place the money in the hands of the Lord Chancellor. You will perceive that the difficulty is to prove the death of James Bell. We can prove that he has never been heard of since I8I8, but this proof naturally rests with us. Now, my dear Sir, my object in writing is to obtain from you whatever documents may be required in order to enable you to collect this money for my mother, and the bearer of this letter will take charge of them and have such papers forwarded direct to me, and I will return them, duly signed, through the firm of Bell & Malcomson, of Belfast.

"You will find the will of my grandfather, John Turney, registered in Lisburn about May, 1816, and this may assist you to prepare the documents. " No doubt, my dear Sir, you will recollect that I was introduced to you by your townswoman, Fanny Fox, in the Spring of 1823, and you arranged some business between Mr. Lamb and myself. For your friendship on that occasion I have ever felt indebted, and I now call on you respecting this claim. No interest has been paid on the account since the death of my step-grandmother, more than seven years ago. Of course, I will gladly pay all costs of your legal assistance in getting the claim settled.

" Yours most respectfully,

" ALEX. T. STEWART."

The years 1833, '34, and '35 were periods of increased success at 257, Broadway. It was said by the wise men of Wall Street—cunning financiers, men who could have run a speculation with Shylock himself—that the great dry goods merchant was worth two million dollars. He had got on the very top of the wave of progress, and, having attained that position, he was not the man to forget taking full advantage of the flood-tide. Nor did he fail to cultivate his mental powers during the stirring times of mercantile advancement. The elementary lessons taught him at William Christie's village school in the Causeway End, his higher class education at Benjamin Neely's seminary in Lisburn, and the classical studies he attended to at the academy of Dr. Skeffington Thompson, of Magheragal, were each and all recollected by the rising merchant, and in after-business hours he delighted in bringing into play the respective teachings of each of the three schools.

A great season of business in New York, and, in fact, throughout all the stirring States of the American Union, was 1835. The great dry goods store, 257, Broadway, had been deepened some five-and-twenty feet, and a couple of stories were added to it—wider frontage was not to be had on any terms—still the volume of business kept so close in the wake of extension that it seemed as if space had no sooner been added than it was filled up. But as the fall of 1836 set in there were heard the distant mutterings of a coming storm in the world of commerce. The weird sages of Wall Street looked out on the atmospheric threatenings with a feeling of dread ; bankers narrowed the range of discounts, and private bill brokers began to look on the ten per cent. tariff for three months' paper as rather moderate than otherwise. The succeeding year commenced very ominously, and the financial tempest that swept over the home of the Stripes and Stars was felt in a greater or less degree in all seats of commerce throughout Europe. At that time the Broadway store was known as that of " A. T. Stewart & Co's." The next in command to that of the great chief was quite equal to the duties of the situation. While the latter moved about through the city picking up bargains which, owing to the extreme tightness of the cash market and the stagnation of sales, were to be had in almost any quantity from storekeepers who had purchased too extensively in the preceding Summer, Mr. Stewart bought immense lots of goods at his own price, and very glad the sellers were to find a ready money customer so willing as he was to clear out held-over stock. It has been stated that his profits on these purchases, as well as on large transactions with Manchester, Macclesfield, and Paris houses, amounted in that year to about two million dollars. The value of all varieties of merchandise had fallen in some cases forty per cent., and, as a matter of course, many of the weaker men in the trade toppled over. Bankers also felt the effects of the panic, and not a few of those arbiters of discount who had been supposed well able to meet all the difficulties incident to the time, were also forced to succumb to the storm.

In the midst of the commercial tempest the head of the Broadway store had advertisements in all the city papers, to the effect that although dry goods had fallen nearly one-half in value he had arranged to have a large proportion of the stock held by his firm marked at even lower figures. Those announcements created much curiosity in the large class of bargain-buyers which abounds in every great centre of humanity, and immense numbers of such worthy people were added to the ordinary customers of the house, and in a few months all that portion of goods was cleared out. Great was the loss in that instance, but with his large floating capital he replaced the stock, buying, in fact, on his own terms ; and, as the better clays came round, the later purchases went off at profits exceeding the highest he had ever realized.

During the later years noted, the sale of Parisian wares had so largely increased that it was considered imperatively necessary to have more direct arrangements with the chief manufacturers of France. A. T. Stewart had by that time become a perfect judge of fancy textiles, whether those of Irish, British, or French make, thus proving the Belfast merchant's aphorism that, " with his high-class educational attainments and aptitude for learning, he would soon be able to master the details of trade." Mrs. Martin and her third husband were then residents of Catherine Street, where they had a furniture store, which was managed by the lady of the house with much of the commercial ability that had marked the career of her distinguished son. Regularly did the rapidly rising merchant visit his mother, and it was with the utmost gratification that he witnessed her success in the business she had so well conducted.

Early in November, 1838, Mr. Stewart left for Paris, where he intended to remain for several months purchasing goods and entering into contracts for future supplies. The money due his mother, and which consisted of the pr0ceeds of the sale of a small farm at Lissue, alluded to in his grandfather's will, had not been paid, and while in the great metropolis of Gaul he wrote as follows to his solicitor in Belfast :—

" 24, Rue Therenot, Paris,

Feb. 18, 1839.

" William Dillon, Esq.

"DEAR SIR, -By last mail from my house in New York I received the form of

affidavit, and, having signed it here before Her Majesty's Consul, herewith

send the same to you. I hope this will suit your purposes, but if not, I

will call on you in July next, on my way home ; but as my visit to Paris has

been so extended, my stay in Lisburn will be very short. If proof of my

signature be required, you can obtain it from John G. Richardson or John Owden, of the firm of Richardson, Sons, & Owden ; and from my correspondence

with their house, my handwriting must be familiar to them. The persons who

hold my mother's money have not treated her well, and I am not disposed to

let them off. She has placed this matter in your hands, with full confidence

that you will do the best you can for her, and with the result of your

professional exertions she will be quite satisfied. When I was in Belfast,

nearly four years ago, I left at your office there a statement, certified by

Thomas Lamb, that N. Dickson, who is since dead, had the money, and his executors

should long since have paid the £140 sterling, with interest since 1825.

With the best wishes for your health and happiness, I have the pleasure to

he,

![]()

" Very truly yours,

" ALEX. T. STEWART."

We give this letter as evidence of the business habits of the man who in his own day, and by his own remarkable abilities, succeeded in achieving a fortune which it required at least two generations of the far-famed Rothschild to accumulate. One of the old axioms of the " copies" which headed the writing-books of the village schools in his early days was, " Take care of the pence, and the pounds will take care of themselves," and, in accordance with that counsel, he looked after his mother's interests in say seven hundred and fifty dollars, as though the sum had been ten times that amount.

In the meantime, the ball of A. T. Stewart rolled onward, and as it did so there seemed still narrowing accommodation for the stock in store and the customers who patronized the house. The American Republic, in the interim, was making such way as to astonish the oldest States in Europe. Brother Jonathan had not only got too big for his boots, but for his nether garments also ; and when we consider what wonders that grandiloquent personage was acquiring he can well be pardoned for his egotism. In the Spring of 1847, the premises of A. T. Stewart & Co. were found totally inadequate to meet the growing extension of their business. Washington Hall, a famous commercial hotel and its mercantile club, were then in the market, and at a cost of sixty thousand dollars, the site was purchased by Mr. Stewart. The area of that building ground comprised two acres, and after clearing away the buildings that stood over it, the erection of the world-renowned Marble Palace was commenced.

A. T. Stewart was a keen, sharp-witted business man— one of those chiefs of the commercial world whom " the unco guid and rigidly righteous " of the pharisaic section of evangelism would look upon as outside the pale of the elect. But amid all the bustle of his anxiety in designing the architecture of his new store, he had his old feeling of nationality towards the home of his birth, Ireland, in 1847, was undergoing one of those periodical seasons of sadness which seem coincident with her history. Two millions of her people were in the very whirlpool of destitution, dearth, and disease, and towards the relief fund which had been got up, the Broadway merchant sent to the Irish Committee, then sitting in Dublin, a contribution of ten thousand dollars.

Stewart's dry goods palace, fronted with marble, was said to be the finest building not only in the model Republic, but in the oldest seats of commerce in Europe. It was six stories high, the altitude from the base of the stores to the top cornice being close on eighty feet, and, as already noted, each of the flats occupied a space of two acres in extent. The original cost of the building was three hundred thousand dollars, and A. T. Stewart designed the building, of course leaving the details to his architect.

It is a peculiar feature in the character of some of the greatest men that superstitious belief forms one of their most powerful motives of action. Sir Walter Scott had the utmost faith in the workings of supernatural agencies. Byron was still more influenced by similar feelings, and A. T. Stewart revelled in the belief of the unseen but powerful influences. In the early days of his commercial career an old Irishwoman kept an apple stall on the footway near the entrance to the old store, 283, Broadway. He had often chatted with her, and was delighted in listening to the ring of the brogue, bringing back, as it did, many recollections of the ancient land at home. When he removed to the great building, in 1848, his ideas of continued prosperity were so connected with the old Celt and her fruit stall that he induced her to bring over her little stall to a site near the Marble Palace, and establish herself there.

New Store

The opening of the new concern formed quite an era in the commercial life of its proprietor, and in that extended sphere of action he set to work with all the energy of a juvenile trader. By this time he had his buyers in all the chief seats of manufacturing industry in Europe, and his immense financial resources enabled him to purchase on the best terms the finest qualities of goods. His high-class education proved very valuable to him, and the sound lessons of mercantile probity he had learned in early life from the good old linendraper, John Turney, as well as the love of truth which Thomas Lamb, his guardian, had instilled into his young mind, admirably fitted him for the inauguration of a mode of transacting retail trade which startled the older men of New York, and gave rise to many prophecies respecting the ultimate failure of " Stewart's mode of doing business."

How much the success of Transatlantic navigation has influenced the wonderful expansion of trade that in 1838 commenced between the Old World and the New could hardly be estimated by any array of figures. On the morning of the 23rd of May, in that year, the men on the look-out at Sandy Hook were fairly puzzled in their conjectures respecting the character of a strange steamer not far in the distance ; and as she dashed onward, and passed up the Hudson, they heard the joyous news that the stranger was the Sirius, an English coaster, and had made the run from Cork in eighteen days. The Sirius, built by Menzies & Sons, of Leith, was only about two hundred feet in length ; but as the pioneer of that magnificent fleet of floating palaces that now bridge the ocean, her name and those of her gallant navigators should not be forgotten in maritime history. Two of the three great men of New York took the utmost interest in the progress of ocean steaming ; these were Cornelius Vanderbilt and A. T. Stewart. The famous Commodore looked on the new source of enterprise with the eye of a seaman, while the Broadway merchant considered it in the light of a vast principle of mercantile progress. When the steamer from Cork made fast her hawsers in New York harbour, crowds of citizens came to gaze with admiration on the handsome vessel, hundreds of Irishmen joined the throng, and the ring of brogue of the Celt commingled with the nasal twang of the Yankee made up a joyous chorus of welcome. During the afternoon of the same day an exultant cry from the throng of sightseers rose in the air, and the shout, " Here comes another ocean steamer," was heard in loud tones ; and, as expectation increased, the Bristol ship Great Western came up, and was berthed near the Sirius. The last arrival was a vessel of two hundred and thirty-six feet in length. She had carried over a number of passengers, and made the run in fourteen days and a-half. Among the thousands of American citizens and European settlers that had assembled on the quays to look at the two noble steamers none seemed to enjoy the sight with greater pleasure than A. T. Stewart. He was able to peer into the dim future, and to see by anticipation what a wide field of accelerated commerce had just then been opened to the Western Republic.

Ten years after these events, and when the marble palace of Broadway was commencing its day of unique attraction, the Cunard Line of ocean steamers was in the first stage of success. The Canada, launched in June, 1848, formed the largest of the fleet. She was two hundred and fifty feet long, eighteen hundred tons burthen, and six hundred horse-power ; next to the Great Britain the largest ship afloat. Edward K. Collins, a native of Massachusetts, and founder of the Dramatic Line of sailing ships that ran for many years between New York and Liverpool, was one of the most energetic of men. His famous packet Siddons ran from Sandy Hook to the point of Cork in fourteen days ; and very proud he felt of that great achievement ; but he said he would build a steamer that would make the voyage from quay to quay between New York and Liverpool in ten days. The Adriatic, one of the finest specimens of naval architecture that ever crossed the ocean, frequently made the passage in nine days and a-half. It was not creditable to the Cabinet at Washington that about 1859, and in a fit of questionable economy, the mail contract was withdrawn from the Collins Line of ocean steamers, the result of that policy being to cause their owner to sell them off. The American Republic has many men to be proud of ; but from the days of Robert Fulton, none more worthy of memorial regard than Edward K. Collins.

I have alluded to these incidents because, in the advancement of commerce

and the progress of industry, facility of communication between the peoples

of different climes and countries, breaks down national prejudices and

accelerates the interchange of com• modifies between races that may have

been antagonistic. The impetus given to American commerce by the successes

of Trans- Atlantic steaming has been something that far exceeds all

anticipation, and even in its earlier stages the effects were seen on both

sides of the ocean. A. T. Stewart and his brother storeowners derived

immense advantage from the regular import of dry goods, the product of every

land in Europe. Distance seemed to have been so narrowed that orders sent to

Belfast, Manchester, London, and Paris were attended to, and the goods were

sent to hand with magical rapidity. The turn-over at the marble palace in

Broadway left the highest average of 257 far in the distance. When an

aggregate of twelve million dollars had been reached, it was considered

quite up to the maximum point; but business developed until that average was

much exceeded. A. T. Stewart had then been in the dry goods trade for more

than one quarter of a century, and his power of arranging the daily duties

of an entire army of rank and file assistants showed how well the algebraic

and mathematical lessons he had been taught by Mr. Benjamin Neely must have

been acted upon in course of his commercial life. But all was not smooth

sailing in the Broadway store. The more narrow-minded of his brother

merchants looked upon him with the utmost jealousy, and did not hesitate to

speak hardly of him, and especially in relation to his economic habits and

the severity with which he came down on any of his assistants that shewed

the least disposition to waste, even in the most trifling instance.

![]()

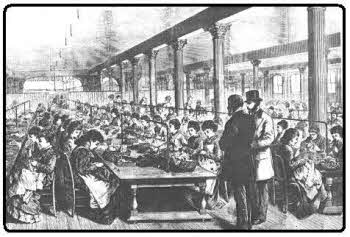

Sewing Room

New York was rapidly advancing in the extent of its population, the wealth of its merchants, and the desire on the part of the fair sex to excel each other in the rich and expensive style of their dressing. The marble palace had become more than ever the resort of the fashionable and the gay of high life, when A. T. Stewart saw that it was time for him to make another move in the upward direction. He accordingly, in 1860, purchased the fee-simple of more than two acres of ground situate between Ninth and Tenth Streets and Fourth Avenue. There he commenced the erection which, when finished, stood, from the level of the street to the top cornice, eighty-eight feet in height, and was the largest store ever erected in any part of the world. It consisted of eight floors, six above and two below the ground, thus making an area of eighteen acres in all.

One thousand young ladies were employed there during the busy season, some cutting-out and others making-up dresses and under garments, and a third of the whole is engaged attending to the sales. These employés were in the receipt of various degrees of salary;. skilled hands had from twelve to fifty dollars, while ordinary employés had from five to ten dollars a-week. Five hundred men were at work in the various floors of the concern, and customers were carried from flat to flat on handsomely fitted-up elevators worked by steam power, and which seemed to move up and down like things of life. Visitors to New York rarely forgot taking a run through - Stewart's store, and, as no one was importuned to purchase, the sight of the wonderful concentration of order and busy commerce had long been considered as one of the city lions. Some years ago, and a short time before Mr. Stewart's death, an Indian chief was taken, accompanied by an interpreter, to see the wonders of the Broadway store. The prairie king was introduced into the departments in which the magnificent dresses and shawls for the Upper Ten were displayed in ample profusion. But, strange to say, he looked with stoical indifference on all the dazzling richness of those triumphs of the loom and the needle. At length his chaperone led him to the engine-room, and for the first time during his visit the red man's spirit seemed aroused to extreme excitement. He watched the five-hundred horse-power engine which raised without the least apparent effort vast piles of merchandise from one flat of the building to another, and kept in motion four hundred sewing machines. At length, in the very ecstasy of savage life, he cried out, " Wonderful ! works herself, and does not kill anyone."

Most readers who have studied the military life of the great Duke will recollect the case of a subaltern whom the commander of the troops, then Lord Wellington, ordered to attend to a certain duty, but, forgetting the stern discipline of the army, took his own opinion as to carrying out the order. Wellington, when aroused, was in the habit of using expletives that would have shocked the saints of Exeter Hail, and in this instance he excelled himself. "How dare you disobey direct orders, sir ?" roared the irate chief. "I thought, my lord—" meekly replied the other. "You thought, sir! Who allowed you such a liberty? Your superior officers think for you, sir, and receive their pay for that. Don't presume to travel outside the law again." It is to be supposed the subaltern took pretty good care not to commit a similar blunder during his day of service.

In the administration of his vast commercial transactions, A. T. Stewart was in his own way quite as great a martinet as the Duke ; he insisted on the most implicit obedience to his orders, and was heard to say that success could not be expected to follow, as it would otherwise do, in any mercantile enterprise in which the head of the house permitted employés to depart from his orders.

About the time of the commencement of the war between the Southern and Northern States of America, Mr. Stewart purchased immense quantities of military stores, and when demand for such goods rose with the requirements, sales were made at very large profits, and yet, as it was afterwards proved, the purchases made by Government at A. T. Stewart's were on much better terms than any that had been bought from other holders.

His firm had many large customers in the South, and much dissatisfaction was expressed by some of these citizens at the evident feeling which Mr. Stewart displayed in favour of the North.

One merchant went still farther than any of the others to whom I have referred, by writing the Broadway capitalist to say that it he (A. T. S.) lent money to carry on the war, and continued to espouse the cause of the anti-slavery party, he would refuse to pay his accounts, and advise other Southerners to do likewise.

Here was a threat of carrying out the system which in 1880 was known in the South and West of Ireland as " Boycotting." But A. T. Stewart was not the man to be intimidated by such threats, and, in the true spirit of patriotism, replied as follows :-

"New York, April 21, 1861.

"DEAR SIR,—Your letter requesting to know whether or not I had offered one million of dollars to the Government for the purpose of aiding in he prosecution of the war, and at the same time informing me that neither yourself nor your friends would pay their debts to my firm, has been received. The intimation not to pay seems to be unusual in the South—aggravated in your case by the assurance that it does not arise from inability ; but let me tell you that whatever may be your determination, or that of others in the South, it will not cause me to change my course. All that I have, whether of wealth or position, I owe to the free institutions of the United States, under which, in common with others, in both North and South, protection to life, liberty, and property is enjoyed in the fullest manner. The Government, to which these blessings are dear, calls on her citizens to protect the capital of the Union from threatened assault ; and although the offer to which you refer has not yet been made by me, I yet dedicate all that I have of wealth, and if needs be my life itself, to the service of my country ; for to that country I am bound by the strongest ties of duty and affection. I had hoped that Tennessee would be loyal to the Constitution ; but however extended may be the secession, or how wide the circle of repudiators, as long as there are men ready to uphold the Sovereignty of the United States, I shall join with them in supporting the Flag.

" I am, yours, &c.,

" ALEX. T. STEWART."

03/02/2012