- Front Page

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- Lisburn's Castle and Cathedral

- The account book of an 18th century Bishop

- An excellent new ballad

- Ballydrain, Dunmurry - an estate through the ages

- Extract from 'A Sketch of the Pelan Family'

- Michael Thomas Sadler - A Forgotten Member Of Parliament

- A Portrait John Dougherty Barbour 1824-1901

- Jigging To The Fiddle At Hilden

- Notes-"In the Gloaming"

- Newspaper Miscellanea - Shaw's Bridge a glance at it's history

- Historical Journals

MICHAEL THOMAS SADLER - A FORGOTTEN MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT

BY J. FRED RANKIN

In Ballylesson churchyard, a rusted iron enclosure marks the last resting place of Michael Thomas Sadler, sometime Member of Parliament and Fellow of the Royal Society. No headstone is to be found; recently the ivy was cleared and revealed a slab tombstone bearing the inscription:

In Memory of

MICHAEL THOMAS SADLER

late M.P. for Newark

who died at the New Lodge, Belfast

July 29, 1835

AE 56

The adjacent grave, also within the iron surround, bears the inscription:

In Memory of MARY BARTLEET

Sister of Mrs. Fenton

Obt May 20, 1847

|

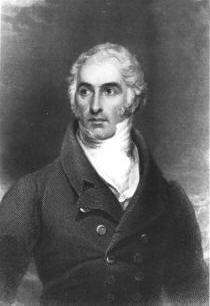

| Michael Thomas Sadler |

Who was Sadler? The entry in the church burial register is clear but gives no clue; beyond the usual notice of death, neither the Belfast News Letter nor the Northern Whig carry any extended obituary which might supply some biographical details. He merits several columns, however, in the Dictionary of National Biography from which source much of what follows has been compiled. A few years after his death, a biography 'Memoirs of the Life and Writings of Michael Thomas Sadler' was published by Robert Benton Seeley; Seeley was evidently a close friend and admirer of Sadler and his work, therefore, does not bear the stamp of objectivity.

Sadler was born in the village of Snelston in Derbyshire in 1780; there was Huguenot blood on his mother's side of the family. There was a well-stocked library at home, where he read widely and consequently was largely self-educated. A love of music, poetry and art developed into the writing of verse, much of which is still extant; he also set many of the Psalms in verse. At the age of 20, Sadler pere set Michael Thomas and his elder brother Benjamin up in business in Leeds and a decade later the two brothers joined in partnership with the widow of Samuel Fenton, an importer of Irish linen in the growing textile town of Leeds. By 1816, Thomas has married Ann Fenton, his partner's daughter, who bore him seven children over the next number of years. So much, then, for his early life and the shaping of his character and personality.

Around this time he became interested in politics and the social problems of his period; business life held little attraction for him and he appears to have left the running of the business to his brother Benjamin. The Leeds Intelligencer, the leading Tory newspaper in the north of England carried frequent articles written by Sadler on social topics. In order to gain experience for his future role he became an active visitor of the sick and destitute and spent much time observing working practices in the burgeoning cotton mills. He supported the government in the wars with France and indeed commanded a company of Leeds Volunteers; he assisted in the 1807 election campaign of Mr. Wilberforce on the tory ticket at York. Throughout this period he remained a staunch supporter of the Established Church and was Superintendent of the largest Sunday School in Leeds which boasted several hundred pupils. As early as 1812, the question of Catholic Emancipation occupied his mind and he spoke strongly against it; a few years later Leeds Corporation found a seat for him which enabled him to gain further experience of government at local level. In 1819 he became a founder member of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society and read to this society papers on various political and economic subjects, amongst them the operation of the Poor Laws and the Corn Laws.

Through his business contacts, Sadler became interested in Ireland and what was known as the Irish problem; this culminated in the publication in 1828 of his book entitled 'Ireland - its Evils and their Remedies'. This book argues against the popular theory of the political economists of the day that the only solution to the problem of over population and starvation was a policy of emigration. Statistically, Sadler argues that Ireland was starved of capital and that in fact more food was exported from the country than would be sufficient for her needs; he pointed out that almost five million acres were uncultivated and should be brought into cultivation using modern methods of agriculture, including the introduction of crops other than the potato. He realised that the extreme dependance on this one crop foretold disaster should it fail, as indeed it did a decade after his death. A century earlier when the population was just over two million (or 71 per square mile), Ireland was an importer of grain; now, with the population just short of seven million or 211 per square mile) Ireland exported over £2m value of grain.

His remedy for this state of affairs was threefold; firstly the introduction of legal provision for the poor and needy; secondly. discouragement of absenteeism and encouragement of residence of landlords and thirdly, because Ireland was essentially an agricultural country, an efficient Corn Law.

The publication of this book brought a great deal of critical acclaim of only from friends and admirers but from those who opposed him politically. It quickly ran through its first edition and was instantly reprinted. A decade later in 1838, after Sadler's death, parliament passed the Irish Poor Law but it was the movement undoubtedly set in motion by the publication of this book which led to this Act being placed on the Statute Book.

In his speech opening parliament in February 1829, the King (George IV) recommended parliament to consider the civil disabilities imposed on Roman

Catholics and whether their removal might or might not endanger the security f the state. This was a direct reversal of previous government policy and

caused the resignation from the Cabinet of Sir William Clinton the Member or Newark in Nottinghamshire, who had been elected specifically on an

anti-Roman platform. The Duke of Newcastle, the principal landowner in the Borough, had become aware of Sadler's views and invited him to stand as

candidate for Newark and so it was that Sadler was elected to Westminster as a Tory, beating an eminent London barrister, Serjeant Wilde, comfortably into

second place. Within days he had delivered his maiden speech against Catholic emancipation; his language was eloquent and impressive:

![]()

"Sir, the measure ought not thus to be presented; it is a choice of evil in preference to good. Banish, Sir, this crooked policy, this disgraceful guide and the choice will be good, present and permanent good. In the ancient path in which your ancestors so nobly trod, there may indeed be difficulties interposed, obstacles to be overcome, as in the paths of duty and of glory there ever have been; but meet them nobly, they will but heighten your achievement and increase its reward. Preserve your Constitution; defend your establishment; become the true friend, the real benefactor of Ireland. Succour and save her by safer, kinder, surer methods than those now proposed and your patriotic efforts will have the approbation of your own consciences, the gratitude of your country and the applauses of posterity".

The text of this speech was circulated as a pamphlet and quickly sold half a million copies. Sadler was instantly famous throughout the country. Altogether during his short parliamentary career of four years, he delivered around ten speeches of some length and whilst they were noteworthy for the depth of their argument, they were more appreciated in the country than they were in Parliament. Although he was reckoned to be the greatest orator of his time, his style was clearly much too long-winded, even for the parliament of these days and he was unable to keep his argument in a compressed and concise form.

The vacation of 1829 was spent with his family in North Yorkshire, where he put the finishing touches to his essay on the principles of population. In this he totally refuted the theories of his slightly older contemporary, Thomas Robert Malthus, who had argues that population increases in a geometrical ratio. Sadler obtained statistical evidence from many countries which proved the opposite to be the case, that population increases in a varying ratio with reference to the density of the existing population. He appears to have been painstakingly meticulous in assembling his statistics from all over the world, no mean feat in itself when one considered the limited means of communication in the third decade of the nineteenth century.

On 3 June 1830, he moved at Westminster "that, in the opinion of this House, the establishment of a system of Poor Laws in Ireland on the principle of that of 43rd of Queen Elizabeth, with such alterations and improvements as the course of time and the differences in the circumstances of England and Ireland may require, is expedient and necessary to the welfare of the people of both Countries".

The death of George IV on 6 June, however, terminated that parliament and his bill got no further; at the following General Election in August of that year he was again elected for Newark. An early measure introduced by this parliament was the Constituency Reform Bill in which it was proposed to enfranchise many of the new towns in the industrial north and reduce the number of rural constituencies. Surprisingly, Sadler took a stance against this bill and actively opposed it; the opposition won the day and parliament was dissolved. In the ensuing reshuffle, Newark was among those seats disenfranchised and Sadler was advised to stand for Aldborough in Yorkshire where the Duke of Newcastle also had influence. He was elected for Aldborough by a comfortable majority.

Around this time, Sadler seemed to lose interest in parliament affairs; no doubt the illness which proved fatal a few years later was beginning to be felt. His zeal and energy were flagging and he proved of little use to his party as he became more and more absorbed in his own pursuit - the condition of the poor. In October 1831, he introduced a bill concerning the grievances and wants of agricultural labourers in England but unfortunately the almost immediate prorogation of parliament prevented its further progress.

In the new season, the question of factory children occupied him and he introduced in December a bill for regulating the labour of children and young persons in the mills and factories of England. Its principal features were to prohibit the labour of infants under nine years and to limit the hours worked between the ages of nine and eighteen to ten hours daily exclusive of meals. The bill became known as the ten hour bill. The second reading was moved in March 1832 and his speech created much comment throughout the country; naturally, however, there was considerable opposition from employers, who maintained that the facts were being exaggerated and a committee of which Sadler was chairman, was appointed to investigate the matter. Among the witnesses called before the committee were a number of working class people, two of whom were actually dismissed from their employment for having given evidence. Whilst he continues to speak at public meetings and demonstrations up and down the country, the strain of all this work took a considerable toll on his health.

Parliament was dissolved in December 1832 and, as Aldborough had been disenfranchised by the recent Reform Bill, Sadler was invited to stand for Leeds. The election was bitterly fought and Sadler lost to his Whig opponent, T.B. Macauley. Thus ended his short, but brilliant parliamentary career. (Two years later he stood for Huddersfield, again unsuccessfully). He continued to take an interest in the plight of the factory children but failing health prevented him taking an active part.

Sometime during 1834, he retired to Belfast and took up residence at the New Lodge, in the district which still bears that name, worshipping each Sunday at Christ Church, then a fashionable and newly built church on the outskirts of the developing town and in the pastoral care of Rev. Thomas Drew, one of the foremost and outspoken preachers of his day; Drew was not noted for impartiality and no doubt Sadler's views on the subject of Roman Catholicism drew the two men together. His illness however, had by now taken a firm grip and he suffered a rapid deterioration in his health; he died on 29 July 1835 at the comparatively early age of 56.

On Tuesday 4th August, the remains of this inestimable man were interred in Ballylesson Churchyard. The gentry and an immense number of the respectable inhabitants of Belfast and the surrounding country evinced their respect for his memory and accompanied him to the grave. A most impressive sermon was preached by Rev. Thomas Drew".

Some days later, a public meeting was held in Leeds to express respect or the memory of Michael Thomas Sadler by his former friends and townspeople. subscription was raised towards the erection of a statue which was to be laced in Leeds Parish Church; I am indebted to the Vicar of Leeds, Canon .J. Richardson, for the accompanying photograph and details of the statue.

Some years ago it was removed from the parish church to an exterior site at Leeds University and is now suffering the effects of pollution and is in

urgent need of restoration. The inscription below the statue reads:

![]()

MICHAEL THOMAS SADLER, F.R.S.

Born at Doveridge in the County of

Derby

From early youth an Inhabitant of this Town.

Endowed with great natural talents,

A fervid imagination, a

feeling heart, and an enquiring mind,

He cultivated, with

success, amidst the distractions of trade,

The Elegance of

Polite Literature

And the severer study of Political and

Social Economy

As exhibited in his works on 'Ireland' and the

'Law of Population'

The display, on various occasions, Of a

Copious Eloquence, peculiarly his own,

In defence of the

Protestant Faith,

Of the rights of humanity, and of the

British Constitution,

Secured him, unsought for, a Seat in the

House of Commons,

And he represented the Boroughs of Newark and

Aldborough

In three successive Parliaments.

He

distinguished himself in the Senate

As the bold defender of

the Institutions of his Country,

And the propounder of

measures

For a legal provision for the Poor of Ireland

And for ameliorating the condition of Factory Children

He died

at Belfast, July 29th, 1835

Aged 58 years.

His remains

rest in Ballylesson Churchyard

By his numerous private and

political friends

This memorial has been erected.

To

hand down to a posterity the name of a

scholar, a Patriot, and

a Practical Philanthropist.

Some 20 years later, on 14 May 1856, a memorial tablet was unveiled in Christ Church by Rev. Thomas Drew; the tablet had been designed by his son, the eminent architect, who was later knighted.

Michael Thomas Sadler left a widow and seven children, at least one of whom took Holy Orders in the Church of England. The Belfast Directory of 1839 lists Mrs. Sadler as residing at New Lodge, New Antrim Road; Benjamin Sadler at 2 Fisherwick Place and Sadler, Fenton & Co., Linen Merchants and Bleachers, with offices at the White Linen Hall and a bleachgreen at Springfie

What better way of ending these few notes on a forgotten Member of Parliament than by quoting from the tribute paid in the Belfast Guardian and Constitutional Advocate of 7 August 1835:

"With feelings of sorrow as deep as we have ever experienced - feelings which we are sure will extend throughout the British Empire, we announce the death of one of the best and greatest men who ever did honour to the name of Englishman. what can we say of a man, whose bright and spotless character affords no shade to set in relief the most brilliant virtues of which human nature is capable - the most splendid talents that have ever adorned our species? By confession of an opponent, but a very competent judge, Lord Plunket, Mr. Sadler was the most accomplished orator heard in the House of Commons by the present generation. But who does not forget his eloquence in the memory of that enthusiasm of benevolence, perfectly without example in the history of the world! As Mr. Burke said of Howard, Mr. Sadler's philanthropy had as much of genius as of virtue. It was a love of his fellow-creatures upon so great a scale, that none but a great mind could have conceived it; and oh! how far was it from that benevolence which is ever suspended in abstraction! It was our happiness and our greatest pride to enjoy his acquaintance; and we can truly say, that whatever he sought for, and wished for, in behalf of the whole human race, he no less earnestly and vigilantly conferred, by manners and conduct, on all within his sphere. Without pretending to any extraordinary sensibility, we declare it too painful to pursue our recollection of the unrivalled charm of Mr. Sadler's society. He has had his best earthly reward - he has 'died the death of the righteous'; and, almost without presumption, we may anticipate that he has realized what a friend predicted of him on that day when he was led into Manchester by 30,000 loving and rejoicing infants. 'Sadler will witness but one more such scene as this, and that will be when he shall receive his reward 'in the resurrection of the just "'.